22/1/2025

環球首席經濟師 Alex Grassino

多元資產方案團隊環球宏觀策略師 Dominique Lapointe,CFA

多元資產方案團隊高級環球宏觀分析師 Erica Camilleri,CFA

多元資產方案團隊高級環球宏觀分析師 Hugo Bélanger

2025年將是全球轉型的一年。因此,我們探討相信將在今年推動環球經濟和市場的五大關鍵力量。請定期瀏覽我們團隊的分析,以獲取更多適時見解及資源,助您順利度過2025年。

僅供說明用途。

從宏觀層面來看,環球增長正處於略為寬鬆貨幣政策與貿易保護主義升溫的交匯點。

踏入2025年,儘管存在潛在的下行風險,但我們對美國經濟增長前景相當樂觀。整體上,我們仍然認為,即使在相對高利率的環境下,經濟增長最終可能面臨一些下行壓力,但美國聯儲局自2024年9月以來實行較寬鬆貨幣政策,料可在一定程度上緩解有關風險,或許使當前經濟勢頭在可預見未來得以持續。

在現階段,我們認為這些動態應可讓美國勞工市場降溫但保持穩健,消費領域的動力亦可延續。我們預期,美國新一屆政府實施的任何新財政政策,對國內經濟的影響不會在2025年下半年及至2026年之前顯現。然而,我們不難想像,環球貿易活動(包括美國向主要貿易夥伴徵收任何關稅)可能會對經濟造成更直接的衝擊。

截至撰文之時,環球大多數其他已發展市場(包括加拿大、歐洲和英國)的增長狀況似乎較美國更疲軟。這些國家地區均受到緊縮貨幣政策的滯後效應及環球貿易放緩(尤其是與中國的貿易)的影響,而有關影響可能會繼續存在。我們認為,2025年或許存在一些互相制衡的因素,影響經濟表現:貿易政策進一步朝著保護主義方向(尤其是美國)所帶來的下行風險,可能會在一定程度上削弱較寬鬆貨幣政策所提供的經濟支持。

日本的經濟軌跡有別於其他已發展市場,因為近期當地通脹企穩,經濟增長前景稍佳,可能有利於日本央行在未來數月繼續推動貨幣政策正常化。然而,我們預期一旦環球貿易摩擦顯著升溫,也會對日本經濟產生影響。

就有關國家的更多詳情,請參閱環球宏觀經濟展望的新興市場部份(第五部份),但整體而言,我們在2025年反復出現的主題將是相對贏家和輸家。從我們的觀點來看,更注重國內市場或與美國關係更緊密的新興市場經濟體,似乎將在未來處於最有利的位置。

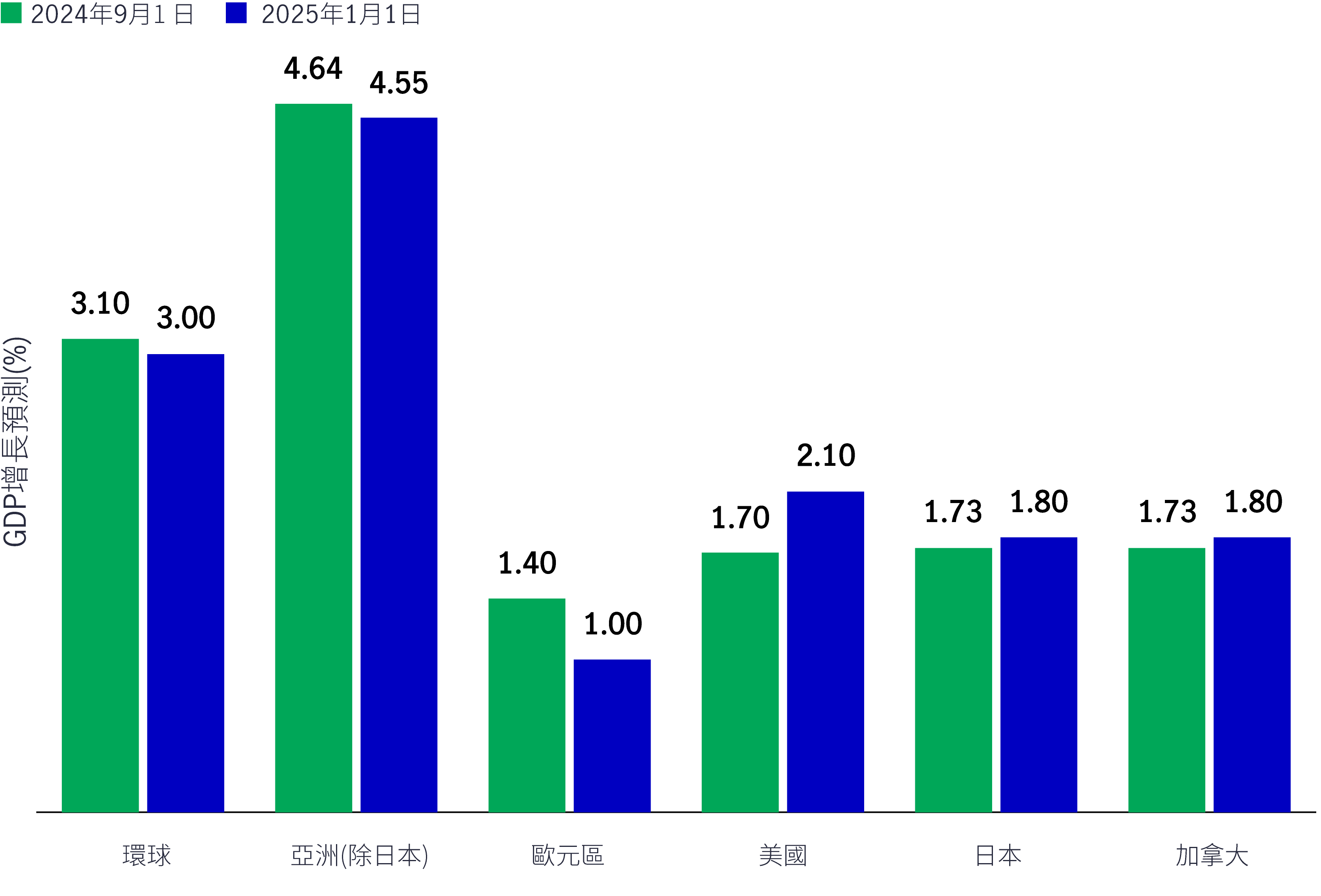

國內生產總值增長預測變化(自2024年9月1日以來)

資料來源:Macrobond及宏利投資管理

踏入2025年,環球大部份央行似乎傾向使貨幣政策朝向各自的中性利率水平(即政策不會刺激或抑制當地經濟的利率水平)。然而,我們預期今年上半年將出現一些障礙,可能阻礙政策循著可預測的路徑,順利走向中性利率。

在2024年11月的美國大選後,聯儲局主席鮑威爾強調,當局將繼續依賴模型及數據行事,而聯邦公開市場委員會成員「不猜測、不推測、不假設」新政治領導班子對政策可能產生的影響。

然而,聯儲局此後的言論更顯猶豫,有兩個關鍵因素或會令當局的政策利率路徑變得複雜,並可能在2025年引發市場波動:

環球貨幣政策收緊,可能在一定程度上抑制加拿大、歐洲部份地區及英國的經濟增長,這些地區的內需近期有所降溫。問題在於,即使在這些已發展市場經濟增長走弱的情況下,高於預期的通脹仍然限制央行實施寬鬆政策(即減息)的能力。此外,聯儲局的減息步伐可能放緩,或會迫使許多央行決定在經濟增長與貨幣走弱之間作出何種取捨。

綜觀已發展市場,日本顯然是個例外,在環球貿易可能放緩的背景下,日本正試圖將其政策利率上調至中性水平。

在新興市場,央行放寬貨幣政策的幅度,可能取決於其對環球貿易的參與度,以及可能需要調整原定計劃,以應對美元相對強勢的程度。

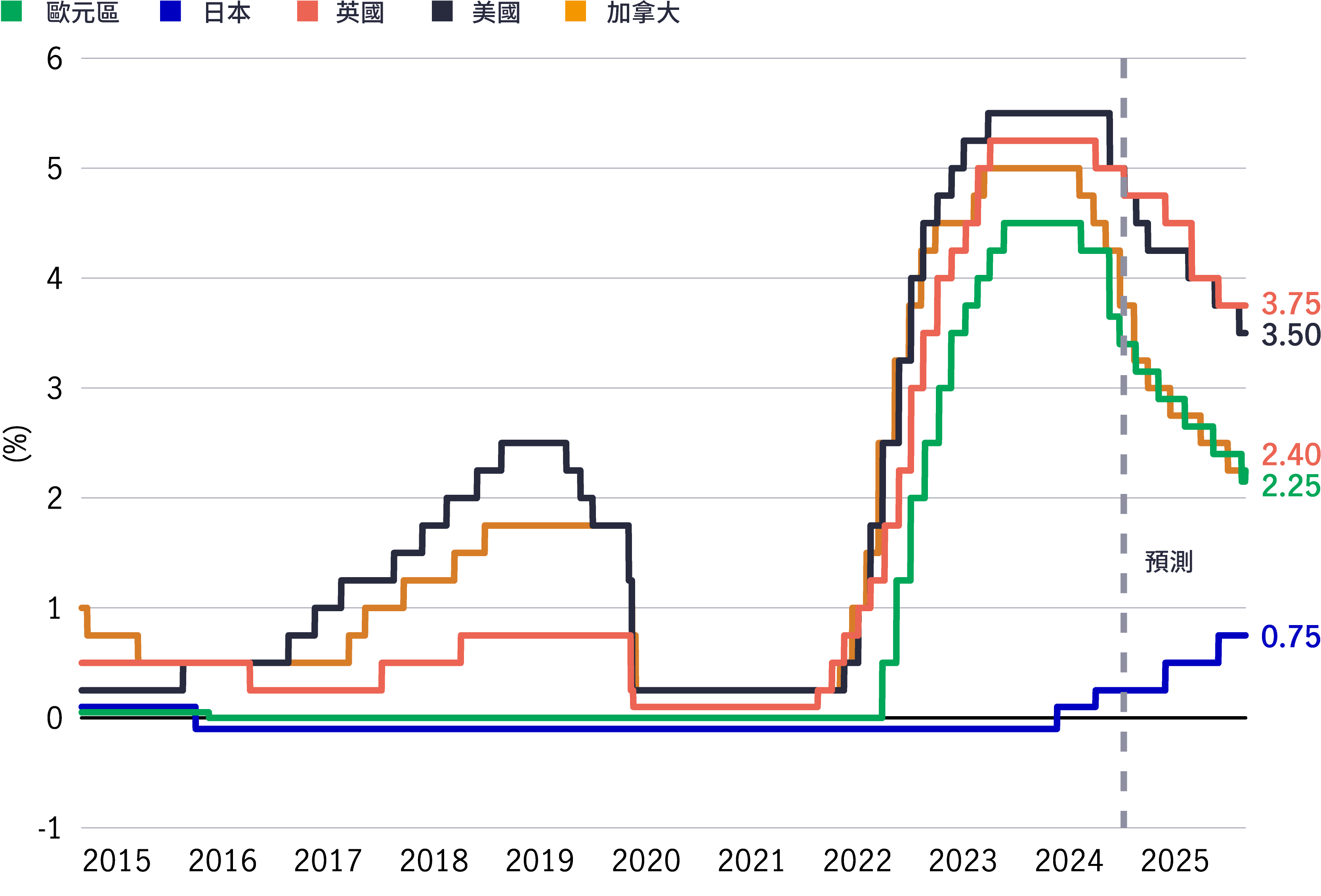

大多數(但並非所有)已發展市場央行的政策利率可能在2025年下調

資料來源:美國聯儲局、加拿大央行、歐洲央行、日本央行、英倫銀行及Macrobond, 宏利投資管理,截至2024年12月9日。

2024年的環球政治背景,包括美國和英國的關鍵選舉,帶來一個熱門話題:不斷增加的公共債務會否在2025年推高政府債券孳息率?

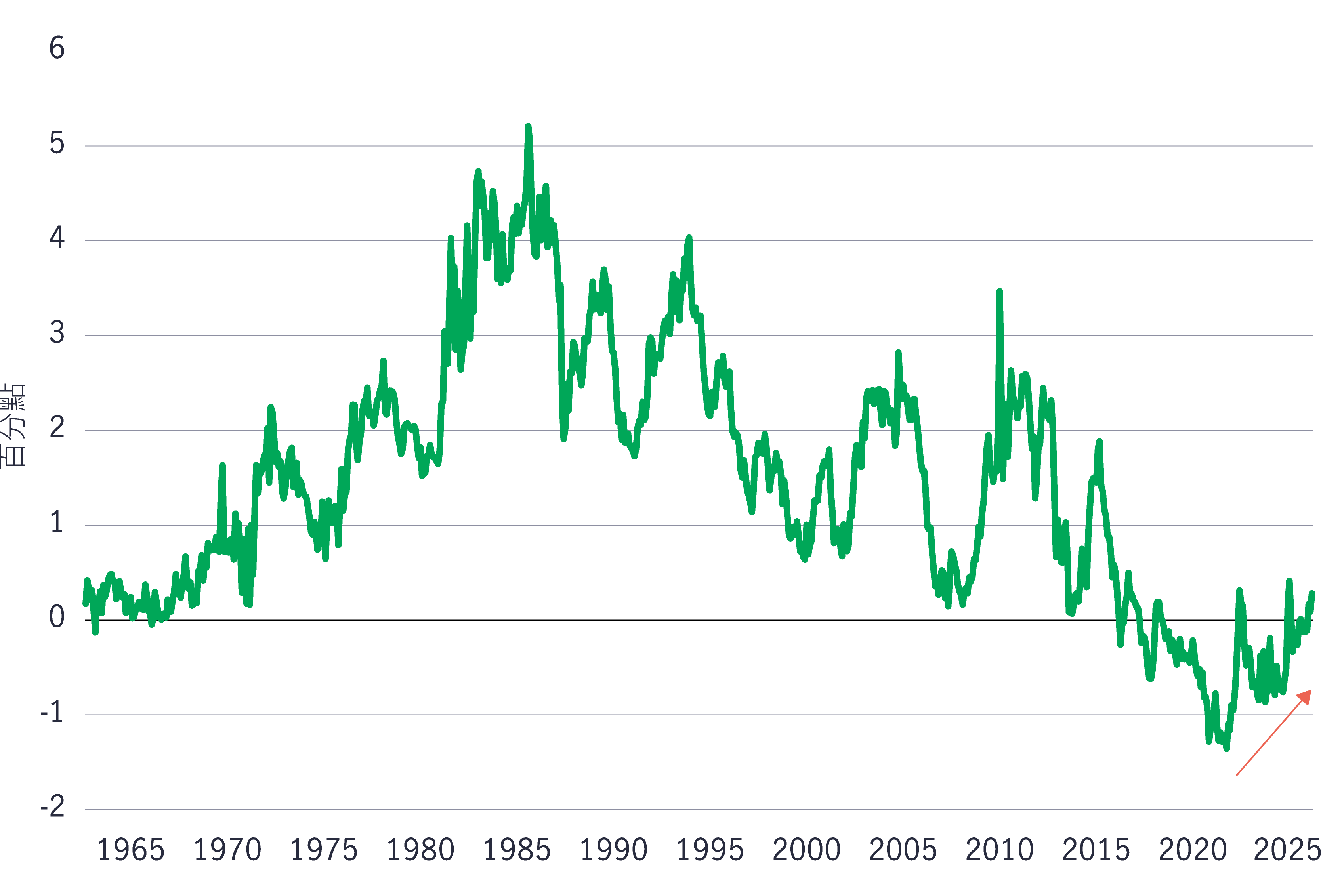

實際上,許多地區的擴張主義財政政策與龐大的預算赤字,已令不少投資者質疑公共債務水平的可持續性,隨著時間推移,這可能導致政府債券期限溢價上升。換句話說,經過近40年下跌之後,投資者對延長政府長期貸款期限所要求的補償可能會開始上升。以下是2025年值得注意的三個元素:

1 巨額赤字將繼續存在。從2008年環球金融危機到與大流行病相關的刺激措施,帶來結構性的巨額預算赤字,導致環球公共債務大量累積。在收入措施不足以抵銷額外開支的情況下,環球政府債務已從2010年的51萬億美元,增加接近一倍至2023年的97萬億美元。基於就業保障和生活成本等其他優先事項,有證據顯示公眾對緊縮政策或財政限制的接受度已經減弱,導致政府控制赤字的意欲不大。

2 利率上升未能帶來助益。在新冠疫情前的時代,政府通常可透過較低利率發行新債,為現有的公共債務再融資,有助於限制償債成本。這在未來可能難以實現,因為我們認為環球利率最終將高於過去數十年的水平,這意味著債券將以更高利率再融資,因而增加公共債務成本。

3 誰會購買債券?我們難以想像,哪類投資者能夠並願意承接過多的公共債務。以美國國庫債券為例,自2009年以來,外國投資者佔流通債務總額的比例已經下降。此外,在沒有發生流動性危機或嚴重經濟衰退的情況下,聯儲局購買國庫債券的機會不大。對價格較敏感的買家(例如家庭及商業銀行)或會出手承接,但可能要求較高的期限溢價,才會繼續為政府開支提供資金。從好的一面來看,相對於公司債券和股票,美國政府債券孳息率較高可能使該資產類別對投資者更具吸引力。

期限溢價會否在2025年大幅提升?

資料來源:紐約聯邦儲備銀行、美國財政部、美國聯儲局、國際貨幣基金組織、宏利投資管理,截至2024年12月19日。紐約聯邦儲備銀行ACM模型估算。

環球製造業和貿易周期對我們的2025年宏觀經濟展望至關重要,因為國內生產總值增長、銷售趨勢和企業盈利的固有周期性大多與這些動態相關。

我們的指標顯示,環球貿易和製造業活動已在2024年第三季見頂,未來數月可能持續轉弱。環球貿易疲軟,反映2025年上半年的經濟增長較為溫和,因為商品需求減少,可能促使企業降低庫存及產量,抑制勞工市場狀況及消費信心。然而,中國的貨幣政策較寬鬆,財政支持較強大,可能會帶來正面的影響,從而緩和這種情況。

隨著2024年美國大選結束,新政府計劃採取更多貿易保護主義政策,為環球貿易增添另一層不明朗因素。舉例說,美國總統特朗普建議對來自中國、墨西哥及加拿大等主要貿易夥伴的進口產品加徵關稅,可能嚴重妨礙環球貿易活動。雖然美國徵收關稅的可能性似乎偏高,但目前尚未公布進一步的細節,因此難以量化關稅對往後環球貿易的影響。

無論如何,美國政治領導班子換屆,進一步加強我們對結構性觀點的信念,即超全球化時代可能已經過去,改變了近40年來刺激各國之間跨境貿易與資金流動,以及持續通縮壓力的環球現象。

我們顯然認為,全球化趨勢不會在短期內逆轉。我們預期,環球貿易動力將在2025年普遍放緩,而非現時的貿易生態系統將會崩潰,這將左右我們的長期增長與通脹預測。我們認為供應面的衝擊與限制,包括貿易政策、氣候相關事件、低碳轉型與地緣政治衝突等,可能會日益影響環球經濟,對通脹水平與波動造成上行壓力。

這類由供應推動的通脹可能需要環球央行採取不同的貨幣政策應對,有別於近期由需求帶動的通脹。

美國關稅似乎會在2025年增加,環球貿易亦會放緩

資料來源:國際貨幣基金組織、世界銀行、美國國際貿易委員會、Macrobond及宏利投資管理,截至2024年11月12日

新興市場可能在2025年面臨阻力,但中國或許是潛在的亮點。

上述宏觀環境或會對許多新興市場造成挑戰,但亦可能為特定市場帶來投資機會。嚴重依賴環球貿易,且貨幣及財政寬鬆空間有限的新興市場國家可能表現落後,而與美國政策較緊密、保持一致,並專注本土的經濟體則應表現較佳。

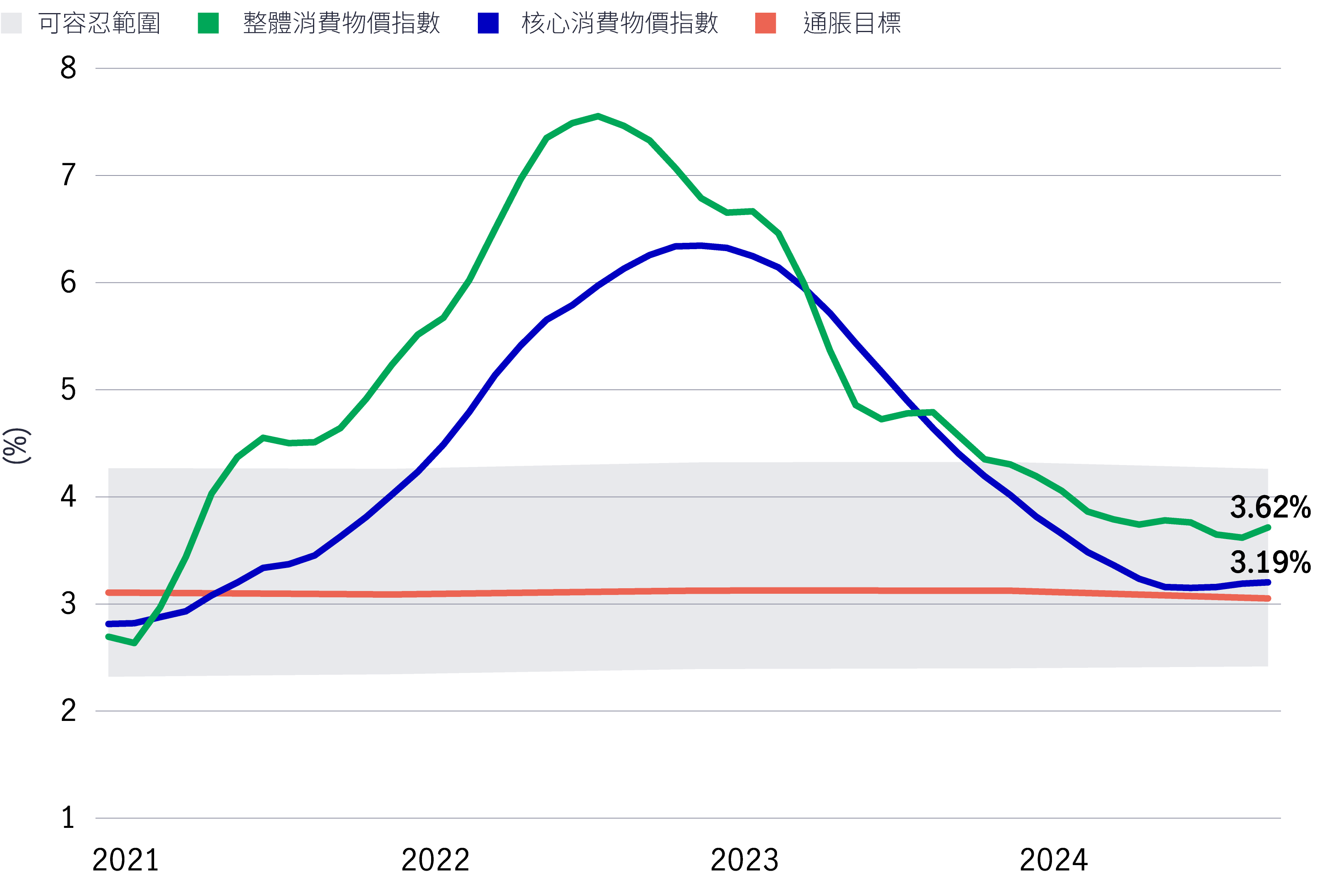

通脹受控及增長疲弱或會促使新興市場進一步減息

資料來源:Macrobond及宏利投資管理,截至2024年11月12日。消費物價指數(CPI)追蹤城市消費者隨時間變化的一籃子商品和服務價格平均變動。投資者不可直接投資於指數。

2025年前景展望系列:環球半導體機會

我們相信擁有多元化且遍布全球、集中於目標行業的高確信度和高品質企業的投資組合,風險調整後的長期回報具備吸引力,這項特性獲得堅固的基本因素、明顯的順勢增長效應、結構性的需求增加以及盈利能見度的強力支持。

2025年前景展望系列:亞洲固定收益

隨著利率走勢改變,在環球利率、信貸及貨幣市場加劇波動的預期下,我們剖析為何亞洲固定收益領域的子資產類別(亞洲高收益債券、亞洲投資級別債券及亞洲本幣債券)可發揮避險及提供機遇的作用。

2025年前景展望系列:大中華股票

在本期「2025年前景展望」中,大中華股票團隊將詳細闡述,儘管存在美國關稅隱憂及地緣政治不利因素,但大中華股票在2025年仍具有更大上行潛力的四大原因,以及4A部署下大中華股票的投資機會。

2025年前景展望系列:環球半導體機會

我們相信擁有多元化且遍布全球、集中於目標行業的高確信度和高品質企業的投資組合,風險調整後的長期回報具備吸引力,這項特性獲得堅固的基本因素、明顯的順勢增長效應、結構性的需求增加以及盈利能見度的強力支持。

2025年前景展望系列:亞洲固定收益

隨著利率走勢改變,在環球利率、信貸及貨幣市場加劇波動的預期下,我們剖析為何亞洲固定收益領域的子資產類別(亞洲高收益債券、亞洲投資級別債券及亞洲本幣債券)可發揮避險及提供機遇的作用。

2025年前景展望系列:大中華股票

在本期「2025年前景展望」中,大中華股票團隊將詳細闡述,儘管存在美國關稅隱憂及地緣政治不利因素,但大中華股票在2025年仍具有更大上行潛力的四大原因,以及4A部署下大中華股票的投資機會。