-

Investor

-

Intermediary

- Institutional

- Insurance

Applying an ESG lens to macroeconomic analysis—a starting place (Part 1)

17 August 2021

Frances Donald, Global Chief Economist & Head of Macro Strategy

ESG factors are playing an increasingly important role in the formulation of investment outlooks—applying a sustainability lens to every element of macroeconomic analysis is now, in our view, mission critical.

Key takeaways

- Integrating ESG factors into macroeconomic analysis enables investors to understand how sustainability issues could influence the way financial markets respond to traditional economic developments and data points.

- Efforts to mitigate the impact of climate change are already having a discernable impact on the global growth outlook in at least one fundamental way: how central banks assess transition risk, which will gradually inform their approach to monetary policy.

- In our view, integrating ESG factors into macroeconomic analysis is more of a necessity than a choice, and failure to do so could risk getting investment calls wrong.

Evolving the ESG conversation

Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing is often perceived as a bottom-up investment approach with a focus on selecting the right companies and attaining an acceptable ESG risk/return profile for the overall portfolio. It’s also closely associated with opportunities in key future infrastructure, technology, or initiatives that will accelerate the world’s transition to a cleaner, more sustainable, and equitable future. But in our view, there’s now a pressing need to evolve the conversation further and broaden the discourse to include debates on how best to incorporate ESG factors into macroeconomic analysis.

To be sure, this involves more than just adjusting, or for lack of a better word, tinkering, with long-term growth and inflation forecasts—that’s a given. It’s about viewing macro events through an ESG lens in a consistent manner, enabling investors to better understand how sustainability issues could tilt the way markets respond to traditional economic developments and data points. In our view, the future of macro investing is tied to the industry’s ability to devise ways to integrate ESG factors into macroeconomic analysis, or we run the very real risk of getting investment calls—tactical and strategic—wrong.

A less-than-straightforward process

Applying an ESG lens to the macro outlook isn’t always straightforward. Naturally, there are quantifiable ways to integrate shifting narratives such as carbon taxes and government spending on green infrastructure that have already been announced into macroeconomic forecasts through modeling, but qualitative judgments are just as important—being able to calibrate global central banks’ evolving perspectives on how environmental and social risks could affect their mandate and the way they think about growth will likely produce a material difference to projected economic outcomes.

Crucially, the drive to incorporate ESG factors and macroeconomic analysis remains at a nascent stage of development—we’re closer to the beginning of the journey than the end, and as the relevant data, policies, and available technology become more sophisticated, so too will our ability to embed them into our outlook.

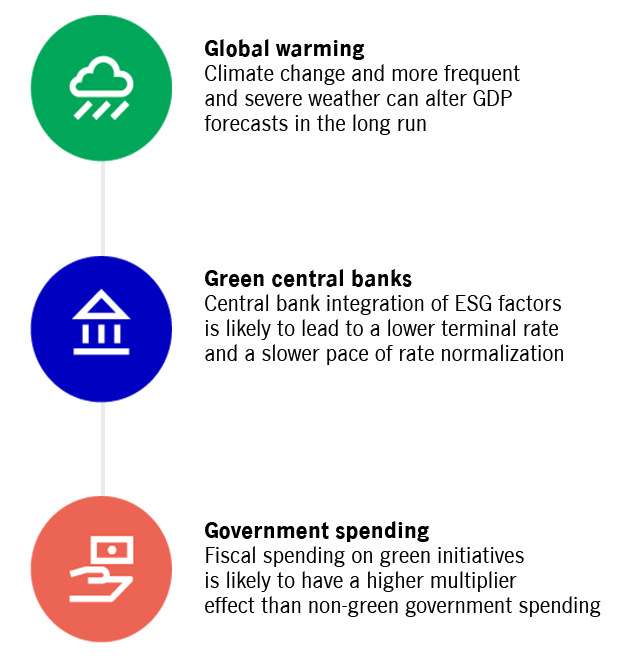

Within this context, we highlight three ways in which ESG factors are already altering our macro perspective and three macro themes that we’re increasingly viewing through an ESG lens.

Climate change and the forecasting process

Climate change is altering the way we assess the global economy

-

Policy Normalisation in Japan: how high will the BoJ go?

Read more -

Here come the tariffs: why it’s too soon to draw conclusions

Read more -

Q&A: The role of Asia-Pacific bonds in an investor’s portfolio

Read more

Source: Manulife Investment Management, July 1, 2021.

1 Impact of climate change differs from region to region

The Paris Agreement aims to limit global warming to 2˚C relative to preindustrial levels¹; as such, many economic forecasters, including us, have incorporated a 2˚ rise in global temperature by 2050 into our models.² This enables us to generate scenarios that incorporate different levels of carbon intensity and changes in global temperatures that ultimately feed into our economic forecast. Broadly speaking, such an exercise has enabled us to observe a nonlinear relationship between productivity and changes in global temperature. For example, we’ve learned that colder regions such as Europe and North America are likely to experience a boost in productivity, largely due to an expected rise in agricultural productivity and construction activity, while the reverse is likely to occur in warmer regions such as Latin America and Asia.

2 Rise in frequency and severity of extreme weather events

A rise in the frequency and severity of extreme weather events can also lead to a slightly different set of challenges in the forecasting process that economists don’t typically come across: While we can measure expected gradual chronic changes in the weather, it’s much more difficult to capture extreme weather events such as typhoons, earthquakes, and droughts—events that can heighten market, credit, and liquidity risks and lead to potential supply chain disruptions as well as demand-side shock. These climate-related risks are also widely expected to drive immigration patterns and create stranded assets. In our view, the rise in the frequency and severity of weather events necessitates the application of a wider confidence band around base economic forecasts.

3 Transition risks

The transition to an environmentally sustainable future is also likely to introduce new forms of risks to our base-case outlooks, both positive and negative. For instance, a fall in clean energy prices—an outcome of technological advancements—could lead to a drop in demand for fossil fuels, a development that could affect the financial health of traditional energy companies as well as banks and insurers that have underwritten loans for these firms. From a macroeconomic perspective, such an event could have implications for productivity, capital expenditure, and the direction of investment flow, among others. Arguably, the wheels are already in motion: The cost of producing solar power and wind energy has been declining steadily, while breakthroughs in carbon capture and sequestration technology could herald important changes in the future.³ It’s also important to take into account transition risks associated with public policy changes—carbon taxes and carbon emission schemes come to mind. It’s worth noting that these policy decisions could have knock-on effects on growth and should be incorporated into macro analysis as well; for example, official income derived from these initiatives that flows back into the economy through wages and associated capital investment. Understandably, some transition risks will continue to fall into the known unknowns category—changes in private sector sentiment and consumer preferences or the unexpected emergence of disruptive business models that threaten long-held industry norms. What this means is that macro analysts will need to pay close attention to changes in sentiment and technology. Incidentally, the very nature of known unknowns implies that a larger confidence band around base-case forecasts, particularly those over a longer horizon, could be needed.

It’s important to note that the three areas that we’ve highlighted represent no more than a starting place—the list is long and will continue to grow. As the industry uncovers more sophisticated ways of capturing and measuring sustainability factors, we’ll all get better at incorporating issues such as coastal flooding, water scarcity, and migration into our analysis.

1 The Paris Agreement, 2021.

2 The assumption that global temperature will rise by 2˚C by 2050 reflects the mitigation policies that have already been announced, but does not take into account additional mitigation policies.

3 “Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2020,” International Renewable Energy Agency, June 2021.